A ‘mass exodus’

Broken, burned out and ignored, nurses are leaving the bedside at alarming rates.By: Elise Kline

When Alycia Flemembaum was a nursing student nearly 10 years ago, she entered the field with passion and excitement. She wanted to facilitate real change for patients as a nurse. Today, she said she feels broken.

Flemembaum works as a labor and delivery nurse at Howard County General Hospital in Columbia, Maryland. When the pandemic first hit, patients flooded in at an overwhelming rate and nurses juggled more than they could realistically handle.

“Patients just kept coming in and coming in,” she said.

By October 2021, she hit a breaking point. She worked countless shifts without lunch or bathroom breaks and was continuously denied requested vacation time.

After coming close to being admitted into an in-patient psychiatric facility, Flemembaum, 40, decided to take a medical leave of absence.

“The majority of my mental issue was because of my job,” Flemembaum said. “It almost destroyed me because nobody was taking care of us.”

Flemembaum recounted her coworkers repeatedly telling her they needed her at the hospital. She said she felt she was simply “a warm body.” As she spent the next month trying to recover, Flemembaum said she felt devastated.

Flemembaum’s experience is not unlike others. Nurses across the country are feeling overworked and under-appreciated. They are suffering on the frontlines from a combination of factors — the rage of the pandemic, a rise in intense burnout culture, increasing turnover rates, and unregulated staff-to-patient ratios.

Health policy experts say regulating minimum staff-to-patient ratios would significantly improve workplace satisfaction for nurses and patient outcomes, but lawmakers continue to be divided on this issue.

There are currently only two states in the nation with statutes mandating safe staff-to-patient ratios, according to the American Nurses Association. Last year, federal legislation was introduced in Congress to mandate nursing staff standards for hospitals, but the bill remains stalled in a referral to the Subcommittee on Health.

Nurses say they are tired of waiting for lawmakers to push forward efforts that could help them.

Leaving the bedside

Janel Crowley, 47, works as a nurse in Portland, Maine at Maine Medical Center in a neonatal intensive care unit with patients who are considered to be fragile. When she walks into her shift surrounded by sick newborns, she is often overwhelmed with staff-to-patient ratios she said are unsafe. Crowley said a safe ratio for the NICU is one nurse to one patient.

“They like to stretch us to three or four patients.”

Crowley said many of her friends in nursing are ready to quit because of the stress and frustration they feel working against these ratios.

Janel Crowley, a registered nurse from Portland, Maine, standing and holding her sign on Pennsylvania Ave. in Washington, D.C. She is one of many nurses who traveled hundreds of miles for the National Nurses March. (Elise Kline).

According to the National Library of Medicine, a safe and healthy nursing staff-to-patient ratio should be 1-3 in teaching hospitals and 1-5 in general hospitals including a senior nurse post.

But for Megan Carroll, 32, a registered staff nurse from Buffalo, NY, she said in her experience, she has worked shifts consistently with no nursing assistants while responsible for eight patients.

“It was unsafe and it was not why I went to school to become a nurse,” she said. She became so frustrated that she quit and later became a travel nurse.

Local hospital emergency room doors in Washington, D.C. For the past two years, emergency room’s like this one have been flooded with COVID patients. (Elise Kline).

A recent 2022 study from Nursing Solutions, Inc., a national nurse recruitment and retention firm, revealed that turnover rates in nursing increased by 8.4% in the last year. The data also showed the rate of nurses leaving the profession nearly doubled since 2017, leaping from 16.8% in 2017 to 27.1% in 2021.

Rachel French, a fellow in the National Clinician Scholars Program at the University of Pennsylvania, said an essential element to understanding the increase in turnover rates for nurses is the labor conditions.

“We’re seeing shortages that are induced by strains on the healthcare system and a mass exodus of nurses due to the poor working conditions,” French said. “If we don’t address the burnout, we’re going to have a profession that’s not able to provide high-quality care for patients.”

According to French’s 2021 hospital nurse staffing study, safer staffing ratios resulted in shorter recovery stays for patients and saved more lives.

There are a number of issues that arise when nurses are handling a heavier caseload of patients, including medicine administration errors and death.

And the weight of these situations often falls heavily and solely on nurses’ shoulders.

“I’ve been put in some really unsafe situations and I don't think it's fair that we're held accountable but nobody else is,” said Samantha Ellis, a 27-year-old travel nurse from Atlanta, Georgia.

Rules and Regulations

California became the first state to implement nurse staffing standards when it passed regulations in 1999. More than two decades later, it remains the only state with ratio regulations for all hospital units.

Health policy experts said the legislation regulating ratios has come and gone federally and at the state level. According to Rachel French, a fellow in the National Clinician Scholars Program at the University of Pennsylvania, regulation is often a triggering word for people.

“I think there’s a lot to learn from efforts to implement safe staffing standards,” she added. “It’s a very politically fraught endeavor.”

According to the American Nurses Association, Massachusetts recently tried to pass a ratio law. While the legislation ultimately failed because lawmakers felt the budgets were too high and the patient outcomes were too unpredictable, they did agree to implement a 1-1 ratio regulation for the intensive care unit.

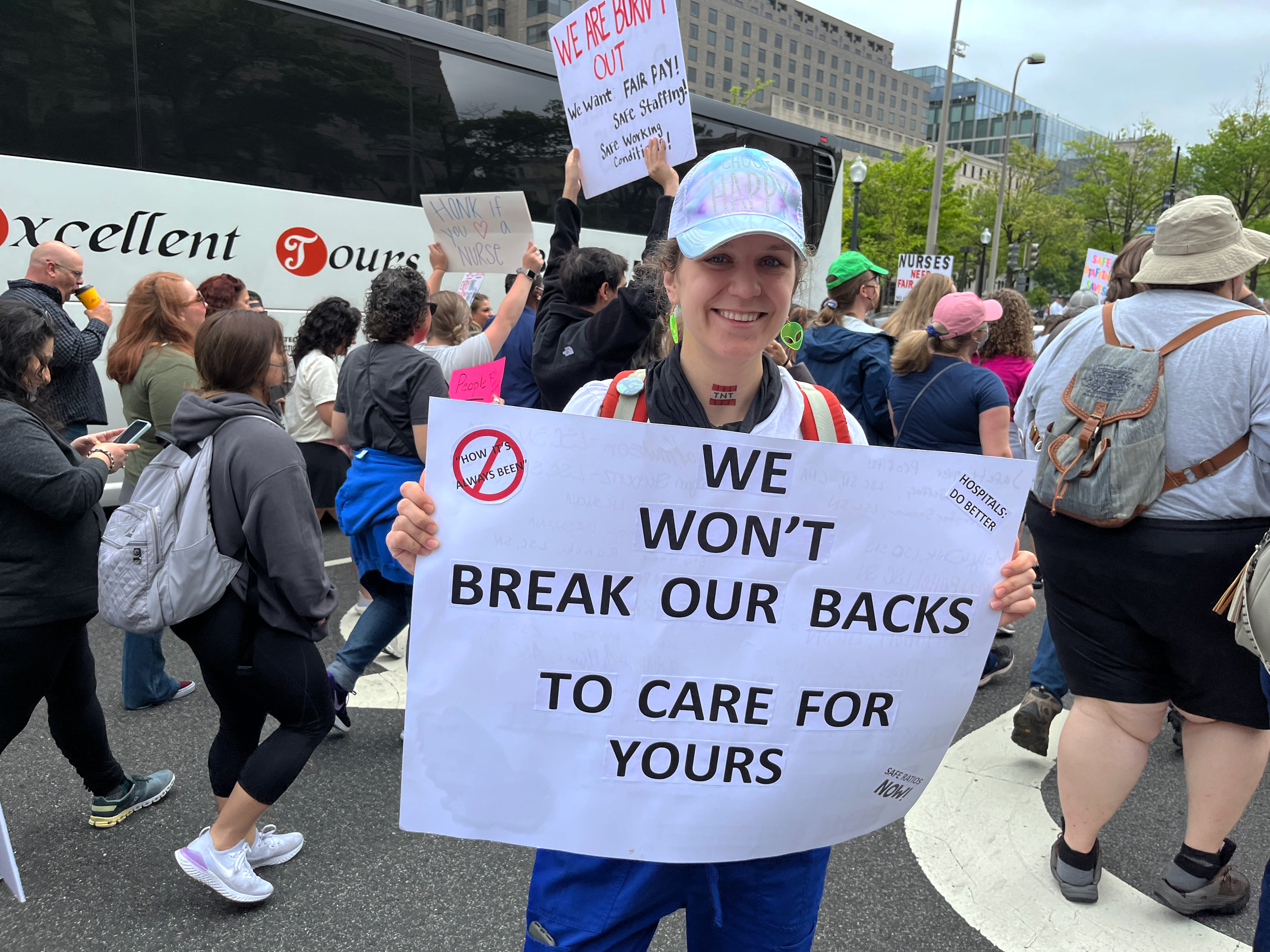

Chelsea McKenzie, a registered nurse, traveled from Florida to march in Washington, D.C. On the day of the march, she brought her handmade sign, her passion for justice, and her advocacy voice to chant with her fellow nurses. (Elise Kline).

French has conducted a variety of studies on safe staffing in her career, where she said strong evidence continued to show how staffing ratios largely impact nurses' workplace satisfaction and patient outcomes. With minimum ratio requirements, nurses not only have a greater bandwidth to care for their patients safely which reduces medical complications and readmissions, but the working conditions feel more comfortable, she added.

But some would disagree.

Jan Emerson-Shea, a spokesperson for the California Hospital Association, said the ratio law in her state is “rigid” and financially challenging. Hiring more nurses to implement these ratios has cost California hospitals a substantial amount of money, according to a 2021 financial analysis from KauffmanHall, which only increased when the pandemic hit.

“We’ve generally learned to live with it. It is the law, but it does definitely tie hands,” Emerson-Shea said.

Patricia Pittman, director of the Mullan Institute for Health Workforce Equity at George Washington University in Washington, D.C., said nurses and other personal care staff do not bill directly for their services as doctors do. Therefore, they are not considered “revenue generators.”

“As a result, hospitals tend to staff as cleanly as possible. And so there’s tremendous variation based on each organization's philosophy and leadership style,” she said.

Nurses feel the financial cost or bottom line of implementing staffing ratios is often prioritized over their and their patient's well-being.

“It’s like dollars and cents over patient safety,” said Flemembaum, who has been a registered nurse for 10 years.

Emerson-Shea argued that hospital financial management and the well-being of staff and patients are of equal importance.

In 2006, two years after the California ratio law officially went into effect, Linda H. Aiken, RN from the Leonard Davis Institute of Health Economics at the University of Pennsylvania sent out surveys that revealed 73% of nurses in California felt their workload was fair compared to 59% in New Jersey, a state without ratio regulations.

Fifty-eight percent of California nurses reported there was enough nursing staff to provide quality care for patients. Aiken’s 2010 study suggested that states with the same ratio standards would decrease the number of surgical deaths.

Before the California ratio legislation was implemented in 2004, Zenei Triunfo-Cortez, a registered nurse from California, worked shifts where she would juggle 20 patients. The minimum nurse-to-patient staffing ratios then reduced that number significantly for her and she was able to spend more time with her patients and their families.

“I had time to really be the nurse that I was trained [to be],” Triunfo-Cortez said. “You were able to sit down by your patient's bedside and hold their hand and alleviate all of their fears and anxiety.”

In addition to improving the quality of care, research shows ratios can be financially beneficial for hospitals. French’s 2021 hospital nurse staffing study estimated 4370 lives saved and $720 million saved in hospitals across New York through a two-year study period.

French said better ratios mean better quality patient care, which means shorter recovery periods and reduced readmissions.

Pittman said there is a tremendous variation in research studies but ultimately evidence continues to show that staffing levels are directly associated with workplace satisfaction, burnout, and patient outcomes.

She also noted the pandemic highlighted the variation and extent to which hospitals manage nurse staffing. Pittman said the flood of patients that came with COVID-19 showed just how understaffed hospitals are across the nation. She said hospitals essentially are forced into crisis mode that could have been aided significantly if “guardrails” on ratios were implemented.

“The government has a responsibility to try and prevent these staffing crises,” she said.

COVID’s Influence

Every day, Chelsea McKenzie, a registered nurse from Florida, felt the weight of patients constantly dying.

“At one point we had 117 vents,” she said, referring to the ventilators used to help COVID patients breathe. “There were many nights where it was like five different codes. So, you’re not bringing anybody back.”

Patients separated by curtains watched each other suffer from the brutal effects of COVID-19.

McKenzie also worried about getting her kids sick. After a shift, she would come home, strip down in the garage of her house, pick up her designated can of Lysol and spray everything before she would enter her house.

Emotionally McKenzie tried to shut down all of her emotions during this time. She said it was the only way to get through it.

McKenzie said overtime was required when the pandemic first hit and compensation for that was almost always in the form of pizza, which she said was infuriating.

“We were getting treated like crap.”

Zenei Triunfo-Cortez, a registered nurse from California and president of the California Nurses Association, who also worked on the frontlines of the pandemic, said it was a “constant battle.” She recounted setting up virtual visits daily via iPad for families to say their last words to their loved ones.

“It was a really distressing time,” she said.

When the conditions worsened through the pandemic, more nurses hit breaking points from burnout and left the profession. As COVID continues to mutate and spread, Pittman said there was a “vicious cycle” upon us.

One nurse from Alabama, Veronica Marshall, said in her 24 years working as a nurse she has never experienced anything like COVID-19. Dealing with the patients of the pandemic and being surrounded by death, Marshall added that some nurses have post-traumatic stress disorder.

“We’re still human,” she said. “And to deal with multiple deaths, multiple code blues, it’s overwhelming.”

Some nurses have left the bedside because of their PTSD.

Sarah Hartmann, a nursing student from Minnesota, held her advocacy sign. Hartmann traveled more than 1,200 miles to march with her fellow nursing students and nursing staff in Washington, D.C. (Elise Kline).

When more nurses leave and hospital staff becomes smaller and smaller, the danger and pressure of managing an abundance of patients and their well-being increases, and consequently, so do burnout levels, experts say.

Triunfo-Cortez said the pandemic exaggerated and highlighted hospitals' staffing issues. She said during the height of the pandemic, some hospitals in California requested waivers for the minimum staff-to-patient ratio regulation. According to the California Department of Health, waivers were granted during Gov. Gavin Newsom’s proclamation of a state of emergency.

“The COVID patients were acutely ill, very sick, and needed a lot of care. And for us to double on the assignment is really not right,” she said.

The waivers did have an expiration date and have since ended. But Triunfo-Cortez said there is still more work to be done by hospital administrators and lawmakers to “beef up staffing.” She noted staffing increases should include registered nurses and nursing assistants. Triunfo-Cortez said she constantly hears the industry line, “there are just no nurses to hire.” She said this is untrue.

“There's a shortage of nurses unwilling to work in an unsafe working environment. There's a lot of nurses to be hired,” she said.

And staffing wasn’t the only problem, she added. Hospitals also struggled to supply the proper patient protective equipment.

“They were much more concerned about the bottom line than the safety of the nurses and other workers during and before the pandemic,” Triunfo-Cortez said.

Overall Impact

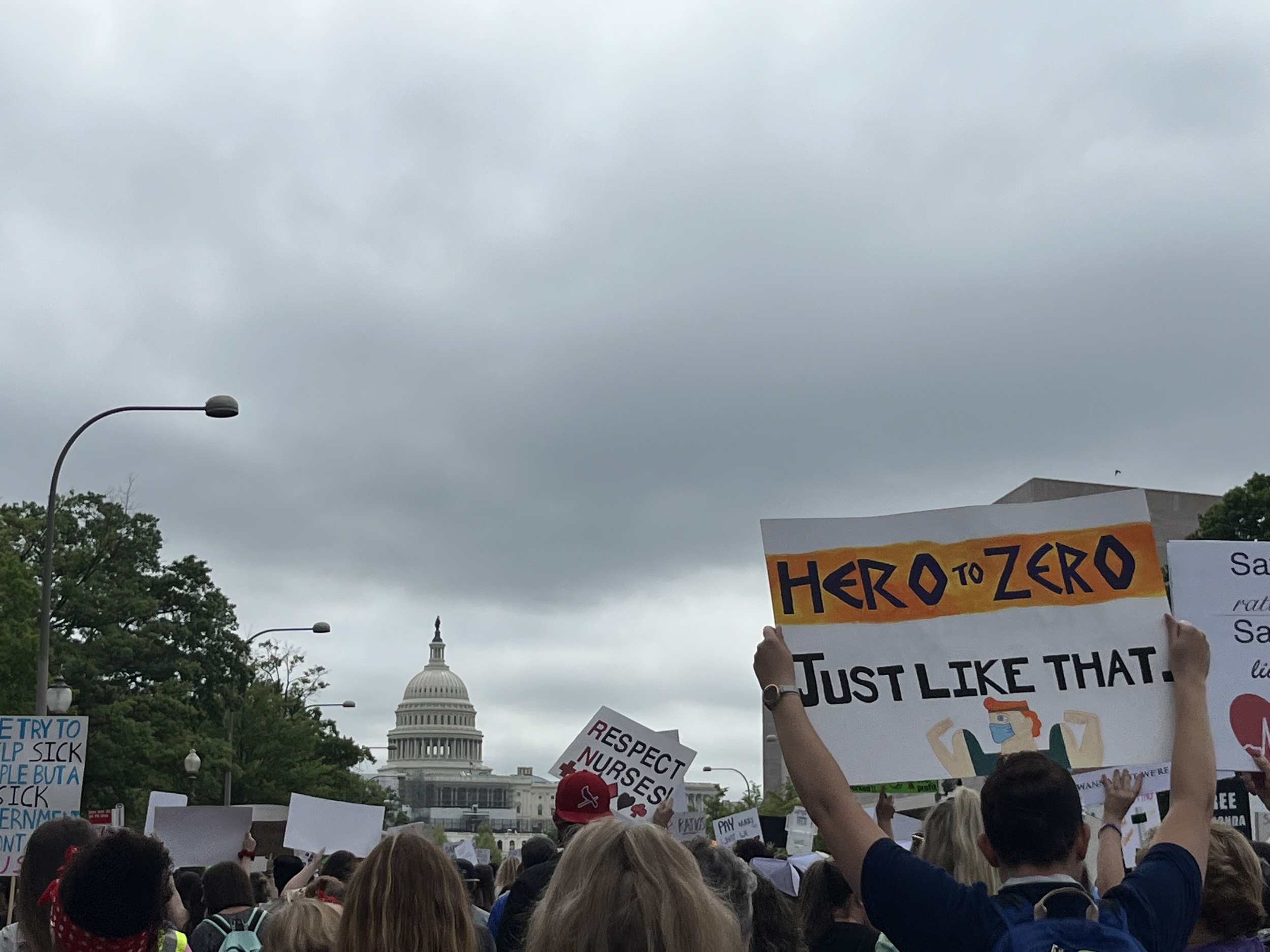

At 8 a.m. on a humid, overcast morning in mid-May, nearly 15,000 nurses assembled in front of the White House. They carried picket signs, they chanted and they walked for hours.

Some traveled locally on the D.C. metro, while others came thousands of miles to participate.

Sarah Hartmann, a 29-year-old first-year nursing student at Lake Superior College in Minnesota, drove over 19 hours in her car, by herself, to advocate with her fellow nurses at the National Nurse’s March.

“Marching today will affect a patient in their lifetime,” she said.

Veronica Marshall is the founder of the National Nurse's March. She started a Facebook group in January for nurses who wanted to gather in D.C. to advocate for safe staffing ratios and fair wages. Within a week, she had recruited over 175,000 members and within three months the march was organized.

“We’re going to continue to try to do what’s right for our patients,” she said.

Kathryn O’Reilly, a local Maryland registered nurse, teared up talking about her experience losing a loved one. She said she feels strongly that unsafe staffing ratios contributed to her grandmother deteriorating as quickly as she did (Elise Kline).

Marshall said nurses provide support for their patients in a variety of ways, including simply sitting by their bedside and listening to them talk. Emotional recovery is as important as physical recovery, she said.

“Some patients just want you to listen to them,” she said. “And when you have a heavy caseload of patients you’re not able to do that.”

For the 29-year-old nursing student Sarah Hartmann, and the thousands of other nurses in Washington, D.C., that day, there was a common purpose: advocating for their patients.

“We need basic protections, we need basic ratios because the bare minimum just isn’t cutting it,” Hartmann said. “The system as it is is unsustainable.”

About this project

Elise Kline is a multimedia reporter. A ‘Mass Exodus’ is her capstone project representative of the completion of her master’s degree in journalism at American University. Prior to this capstone reporting project, Elise has researched and reported on public health, public policy, and gender inequality. She created A ‘Mass Exodus’ to take a deep dive into the impact of burnout culture and staff-to-patient ratio regulations. She spoke to several experts who said that legislation to regulate staffing ratios has come and gone at both the state and federal levels, but still, California remains the only state with ratios in all hospital units. This project uses data, expert analysis, and anecdotal evidence to assess how hospitals, nurses, and patients are affected.